CFO As Storyteller

Last Week’s Panel Talk: CFO as Storyteller

At last week's Annual Sequoia Grove Conference in SF, I had the opportunity to speak on a topic that’s been central to my career: "CFO As Storyteller." The room was filled with over 100 Finance and HR operators, ready for what many might have expected to be a checklist-style presentation on how to become a great CFO storyteller.

But instead of handing out a neatly packaged list of steps, I decided to take a different approach—one that modeled the essence of storytelling itself. My goal was not to give answers but to engage the audience members as characters in their own story.

The result? A lively and interactive conversation where we explored not just the mechanics of storytelling, but the heart of what makes any story compelling.

What Makes a Great Story?

Before diving into how a CFO can become a great storyteller, I asked the audience to reflect on what makes a great story in general. After all, being a storyteller is in our human DNA. Our ancestors sat around fires and learned from each other through the art of storytelling to make sure their tribe could learn fight or flight and several other lessons.

I posed several questions to set the stage:

What was the last great story you read or watched in theaters or on Netflix? Why was it such a a great story?

Now, what was the last story you stopped reading/watching? Why?

Do you remember a story where you were so deeply absorbed in it that you lost yourself in it and felt like you were there?

That’s the power of storytelling. It doesn’t matter whether the story is film, television, your favorite novelist, your company, or finance, certain storytelling elements remain universal.

Great Storytelling Elements:

Journey and Destination: Every story should have a journey, with a clear destination or outcome that matters.

Character Connection: A relationship with the characters is essential. Why should we care about the characters in the story?

Conflict or Drama: Without conflict, there’s no tension and no reason to engage. One of my favorite sayings? “No Conflict? No Interest!“

Risks and Opportunities: Great stories involve risks, challenges, and opportunities—and the hero’s actions to navigate them. The Hobbit was one of my favorite childhood stories.

Heroes and Villains: Every story needs one or more heroes who take action and a villain who is trying to stop you from your journey.

The CFO’s Storytelling Framework

Once we had a shared understanding of what makes a great story, I introduced the challenge of applying that framework to the role of CFO. As finance professionals, we are often expected to be data-driven, pragmatic, and—let’s be honest—a little boring. But in reality, our role is to tell one of the most critical stories of any business: the financial story.

To help the audience connect with this idea, I posed another set of questions:

What is your financial journey? Your financial destination?

Why does that destination matter?

What investment opportunities are you striving to achieve?

What critical activities will it take to achieve these opportunities?

Who (characters) do you need to take you there?

What are the opportunities, obstacles, or conflicts along the way?

Do you have a financial roadmap to show the future financial journey that includes key milestone markers on the map to help communicate how you'll get there?

What are the course correcting tools or weapons you are bringing on this journey “just in case” you stray from your desired path or face those villains?

This isn’t just about making numbers sound interesting. It’s about creating a narrative that resonates with different audiences—whether that’s your CEO, your board, or your employees. Each of these audiences tends to care about different aspects of the financial story and each audience listens for different language in your story.

A CFO needs to translate financial information into similar but different narratives with slightly different language to properly connect and engage with these diverse audiences.

The Power of Storytelling: My Mozilla Example

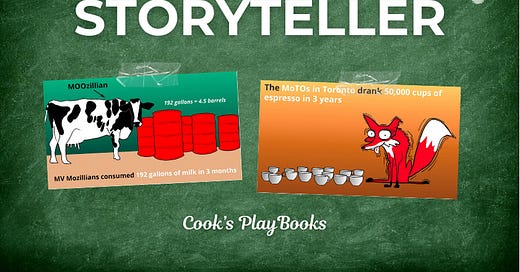

To illustrate these ideas, I’ll now reshare a story from my time as CFO of Mozilla. Shout out to any Mozillian reading this and who remembers this talk in 2016 - Hawaii All Hands. Please respond in the comments or on LinkedIn if you remember this talk.

That year, I wanted to encourage our employees across 12 global offices to take greater ownership of being good financial stewards of the company’s resources. But instead of giving a dry, data-heavy talk about budget management, I decided to focus on relatable and engaging financial elements they should recognize.

I took something as mundane as the monthly kitchen invoice—line items everyone consumed everyday—and broke it down in terms everyone could understand. I shared some surprising “kitchen metrics,” such as:

How Many Gallons of Milk Mozillians Drink Worldwide Per Month

How Many Pounds of Coffee Consumed

Quarts of Blueberries

Pints of Kombucha

Below are a few of the actual “Fun Facts” slides from that presentation:

But I didn’t stop there. I dug deeper, creating a set of unit economics metrics for these items and then boiled it down to the “Average Price Per Office Person” for each item.

I know what it’s like to be in an audience like this when a financial leader tries to influence the company with a line like, “We are spending too much on bringing food into the office,” and then showing a single line of spending called “Kitchen Expense” (or equivalent) and then telling the audience, “We are spending over $1M on our snacks and drinks alone, and we all need to reduce this expense.”

The problem for me, and likely for you, in this approach is the audience members have zero context whether this one number (“Kitchen Expense”) is good or bad? $1M sounds bad? But is $1M high or low for the size of our company? And what comprises “Kitchen Expense” anyways? There’s so much missing contextual data. More importantly, the connection to the audience gets lost.

Incomplete data + no context = No story. No story = no influence.

I didn’t want to be that CFO so I approached the problem at an interesting level of details (coffee, milk, bananas, kombucha, etc.) and then built up the numbers from there for each of the 12 offices and then the whole company’s kitchen expense of 1,200 employees.

The final breakdown showed we were spending roughly $5 per office person per day at each of our offices. I asked the audience to do quick math. $5 per day x roughly 800 people in offices daily (not everyone comes in everyday - even then) x roughly 22-23 workdays per month. The human audience calculators came up with $90K USD per month (correct!) which globally equates to over $1M annually for just basic kitchen snacks/drinks. Note, this did not include employee lunches or other meals brought in on a regular basis. Hmmm….$5 per day per person. Now the audience had real context and the conversation could begin on the opinions of whether that was figure was high or low. The financial conversation could now properly begin.

Mozillians came up to me afterward and throughout the week telling me how interesting, fun, and memorable the financial talk was. The best part was they repeated some of my “fun facts” and started sharing the story with others.

In subsequent months, the conversations developed of whether we really needed the Kombucha at $5 per bottle and eventually various office cohorts began taking financial ownership of each of the offices kitchen expenses and making better choices.

Be the Director of Your Own Movie

Think of any story you are developing with you as the Director of that movie. If you are a Head of Finance or CFO, your Director role in that movie is not to just deliver numbers but to craft a compelling narrative where the risks and opportunities intersect with the financial data. Your success as the “Director” (CFO) is not just in the quality of your numbers, but in the audiences interest level of your financial storytelling and whether your story is credible and reasonable.

While CEOs are often given a “hall pass” to be overly optimistic, CFOs must tell a more grounded story—one rooted in:

Quality of Thinking: The rigor behind your financial analyses.

Truth Telling: Being straightforward and transparent, even when it’s difficult. Guide your audience through minimum and maximum ranges to highlight the range of risks and opportunities.

Transparency: Let the audience see not just where you are in your financial journey (“We Are Here”), but also the path you took to get “Here” and then where you’re going next (“Going There”).

The CFO’s Balancing Act

One of the other CFO panelists in the discussion correctly reminded the audience to always balance optimism with realism when acting as CFO Storyteller. He said, a CEO can get away with painting a rosy picture of the future, but a CFO’s role is to ensure that the story holds up under scrutiny. This means threading the needle between strategic vision and the financial realities of the current situation.

It’s easy for a CFO to fall into the trap of data dumping—sharing endless numbers and hoping that the audience will understand their significance. Great CFO storytellers don’t do that; they craft a financial narrative that makes the numbers meaningful, relatable, and actionable.

For example, when talking to employees, the CFO might emphasize how financial milestones will translate into successful benchmarks for revenue growth, cash burn, cash on hand, the next round of financing, and overall investor interest. With the board, the story might shift to focus on capital efficiency, risk mitigation, or growth investments. And for your 1:1 with your CEO, it’s likely about aligning the company strategy with the company’s capabilities and the actual timing of achieving the CEO’s broader vision of the company’s future. Hint: It will take longer than the CEO thinks!

Bringing It All Together

In closing, I encourage everyone to think of storytelling as an integral part of their role.

It’s not enough to be great with numbers. CFOs must also be great communicators, using the timeless art of storytelling to connect the dots of data between strategy, structure, and execution.

And while there’s no simple 5-step checklist for becoming a great CFO storyteller, the key lies in blending age old storytelling fundamental elements—character, conflict, risk, opportunity, heroes and villains—with the unique financial insights that only a CFO who sits at the unique intersection of company data can provide.

As you reflect on your own role, ask yourself:

Am I the director of my own company’s financial story?

Do I engage my audience, helping them see not just the destination, but the journey to get there?

Do I speak the audience’s language and craft the story to what is interesting for them?

Is my story believable, compelling, and engages the audience to take action?

Is your financial story memorable? Did you give you audience less than a handful of insights and soundbites they can easily share so the story can be passed along easily to others?

In the end, becoming a great CFO storyteller is about both numbers and narrative—to bring your audience along a financial journey with you as the “Director of the Movie Financial Report.”